With winter being in full throes (despite the fact it hasn’t “officially” started yet), one signpost constellation is Orion the Hunter, which magesitcally covers a rather wide area of the southern sky.This constellation is full of lore and myth from different cultures. But that aside, it’s a wonderful image on the tapestry of the night sky through the winter. And it’s the target of many amateur astronomers and astrophotographers due to its myriad of nebulae contained therein.

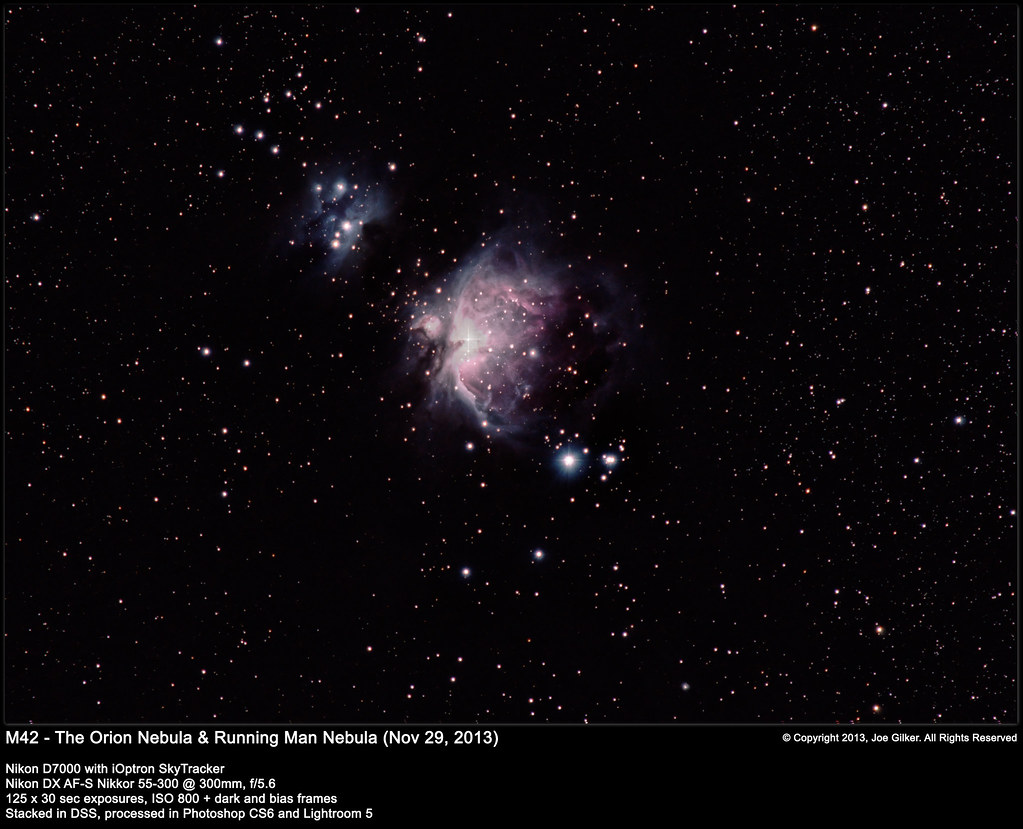

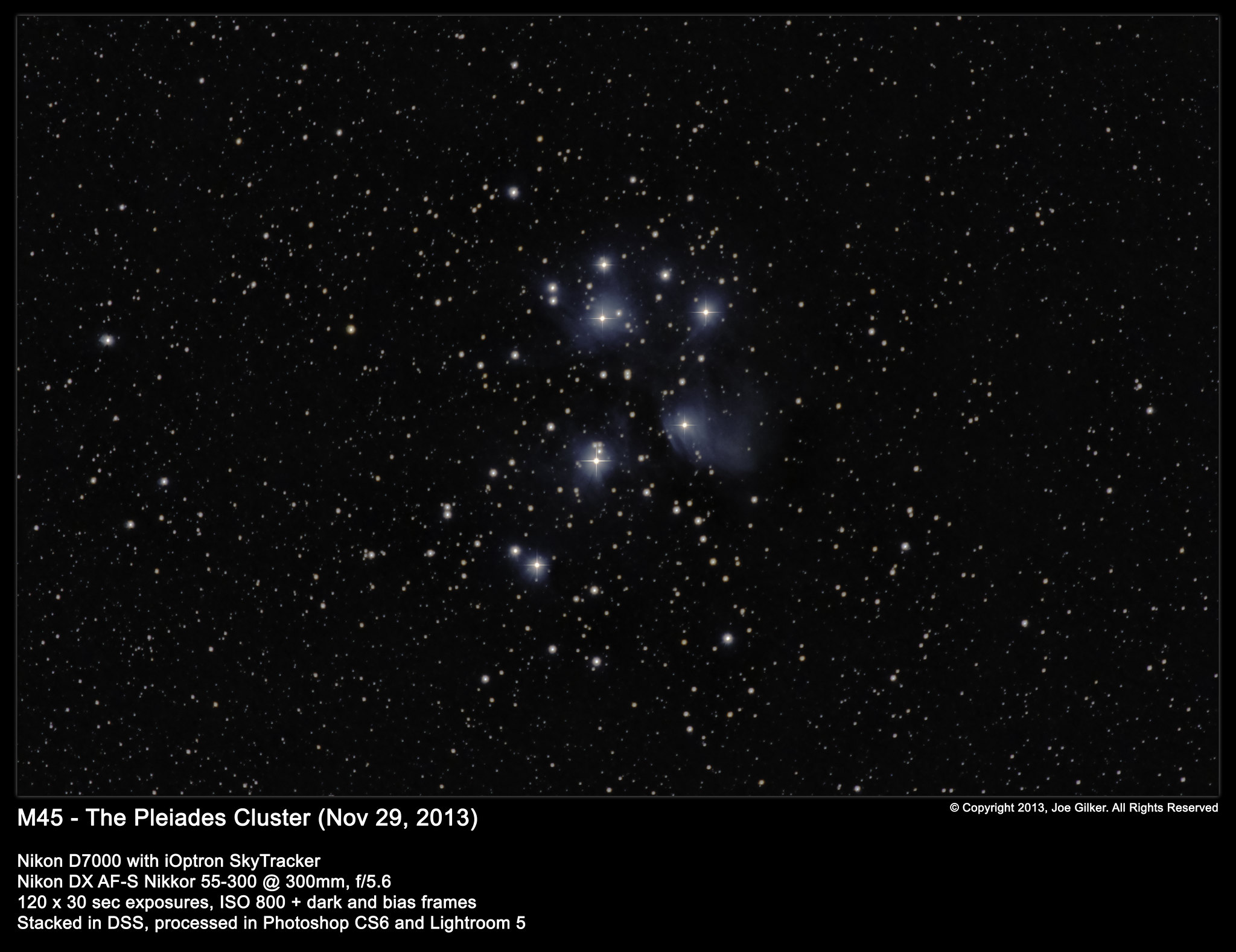

I’m really not able to find a definitive answer as to how many nebulae it contains. Figures tend to range from 10-20, depending on who you ask. Either way, there’s no shortage of stuff to see. The Great Orion Nebula, the Running Man Nebula, the Flame Nebula, The Horsehead Nebula, and Barnard’s Loop are among some of the wonderful sights that can be seen and photographed. It’s a cornucopia of targets for those willing to search them out and patient enough to find and perhaps image them.

Through the winter, I’ll be making several of the well-known objects in Orion my target. I’ve already started with the Orion and Running Man Nebulae, as well at the Flame and Horsehead. Both have been featured here in previous installments of my blog. All are simply 1 hour’s worth of 30 second exposures at this point. I’ll be adding more data to those over the coming months.

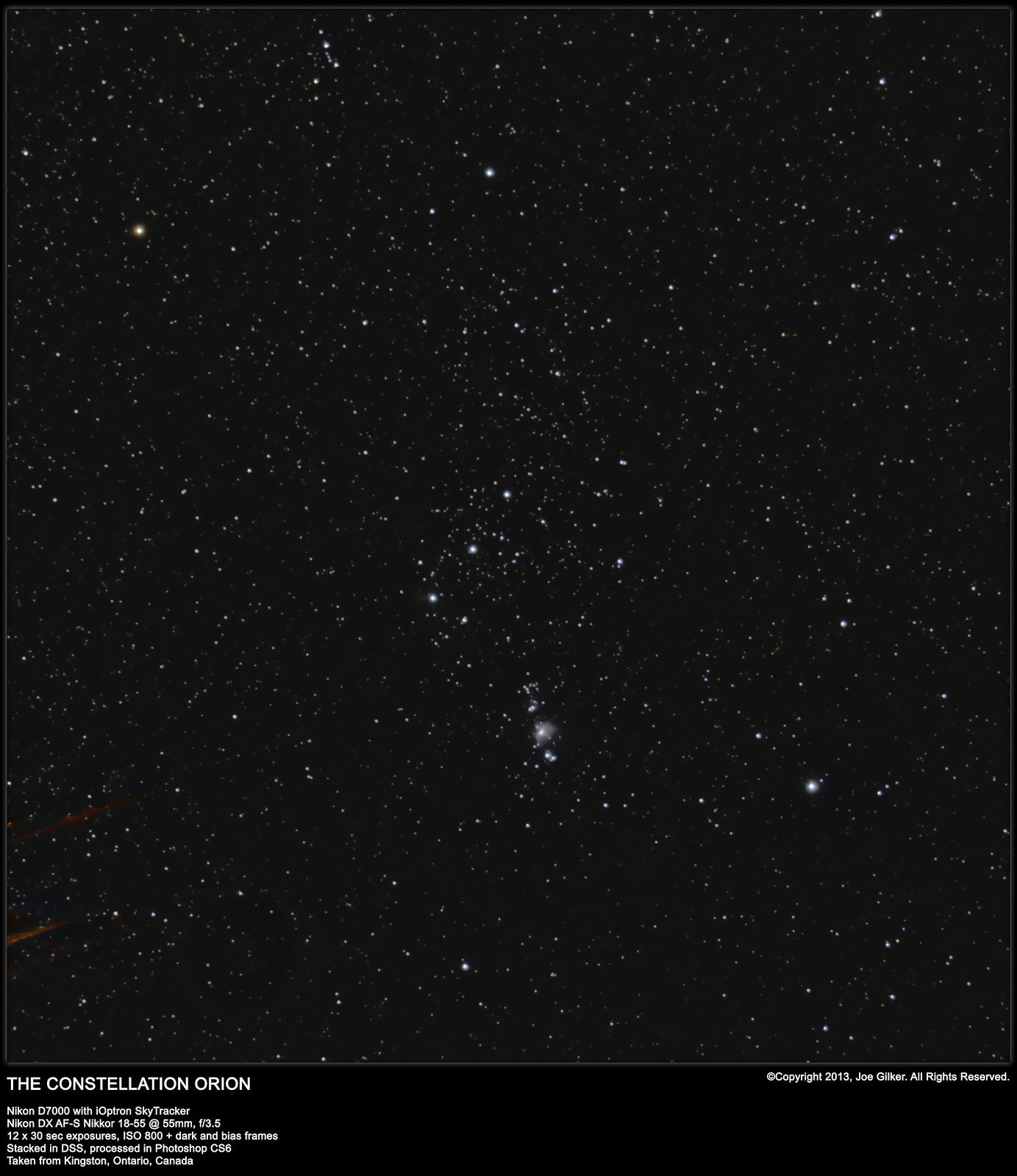

But on a very cold evening a few nights ago, I stepped out with my camera and SkyTracker. The seeing was about 3/5 with a 60% moon in the western sky. I decided that photographing the deep sky objects wasn’t going to bear great fruit, so I figured I would try to catch the entire constellation in one image. I popped on my 18-55mm lens, aligned my mount, and fired off a bunch of 30-second subs, darks and bias frames.

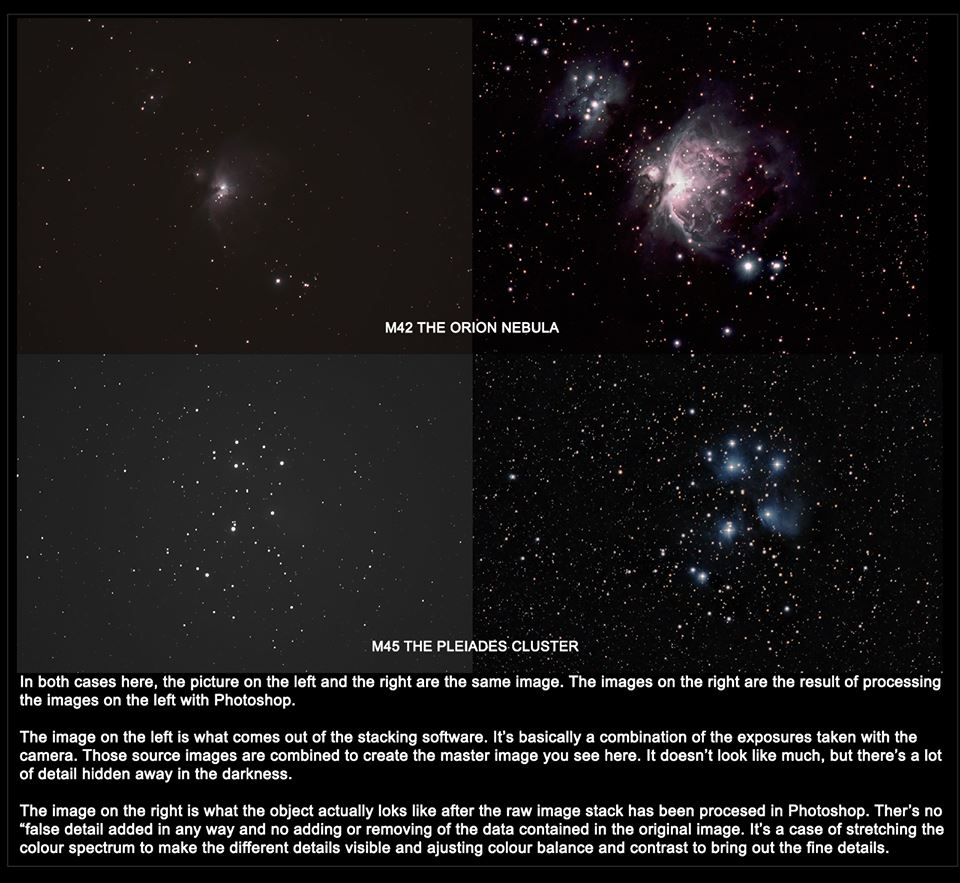

The resulting subs didn’t look like much. Once stacked, the light pollution and gradient in the background made me think that this would be a lost cause, can be seen by this image. The trees in the foreground weren’t a big issue, as I planned on cropping the image anyway.

|

| One of the subs (light frames) that was stacked for the final image below. Jupiter is visible in the upper left corner. |

Then it came to processing the image. I was able to remove the gradient and get a nice neutral, dark background. It actually turned out much better than I had anticipated. Betelgeuse shone magnificently. M42, the Orion Nebula was clearly visible, and I even managed to get a faint hint of the Flame Nebula. Overall, I’m very pleased with the results of this session.

|

| http://www.flickr.com/photos/crunchmeister/11333572226/in/photostream/ |

Clear skies.