Since I started doing astrophotography, I’ve been jokingly referring to it as the “dark arts” to my friends and such. Without knowing any better, most would assume I call it such because it involves taking pictures in the dark. That may be true to an extent, but it’s not why I call it that.I call it that because it’s all about bringing light out of the darkness. It’s about making the invisible visible. It’s about exposing what would otherwise be hidden. And to those who don’t know how it works, it may as well be witchcraft. Actually a couple of hundred years ago, this kind of talk would probably have gotten me burned at the stake.

The picture taking process is really just a small part of it. And really, that’s the easy and most “hands off” part of the process. Once the mount is set up, target found, the camera settings are all adjusted and focus is set, the picture-taking process is a pretty brain dead affair. With the proper equipment like a remote intervalometer / shutter control, it’s actually completely automated.

The “dark arts” part comes from processing the photos. First there’s the stacking process with DeepSkyStacker or whatever other stacking software one chooses to use. This produces the master image that then gets edited in Photoshop (or whatever image manipulation software one chooses to use) after the fact. As long as you have good source data from an in-focus camera with accurate star tracking, this is where the black magic really happens.

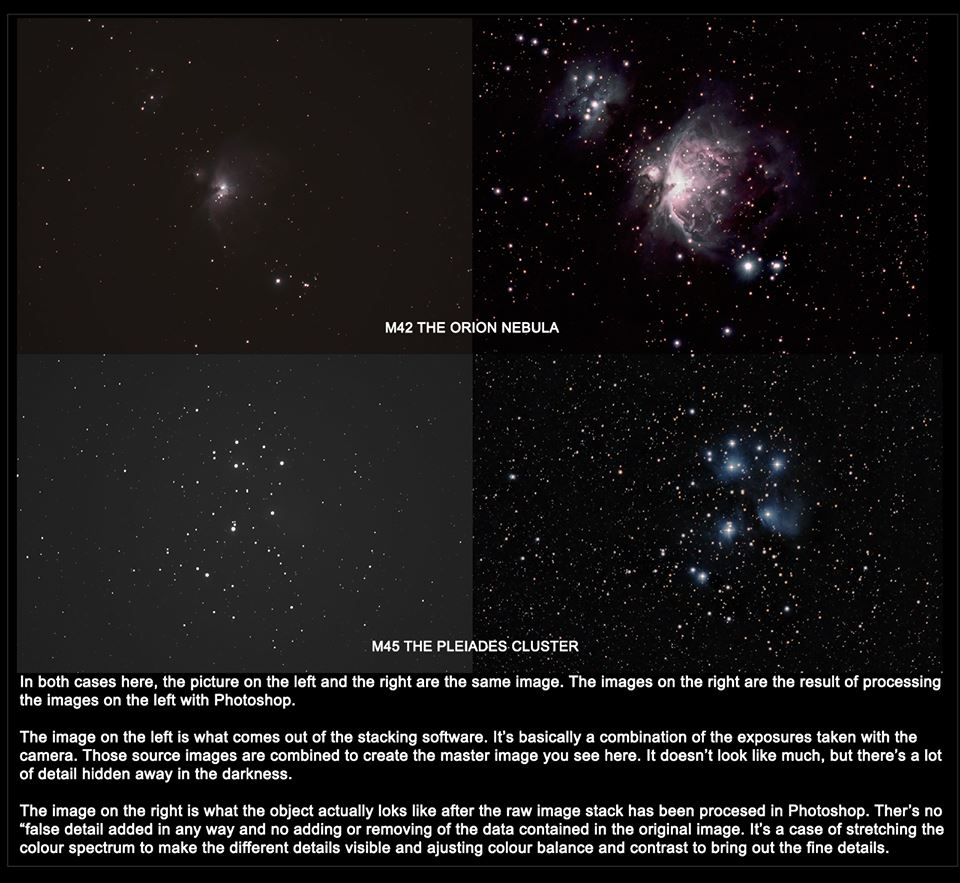

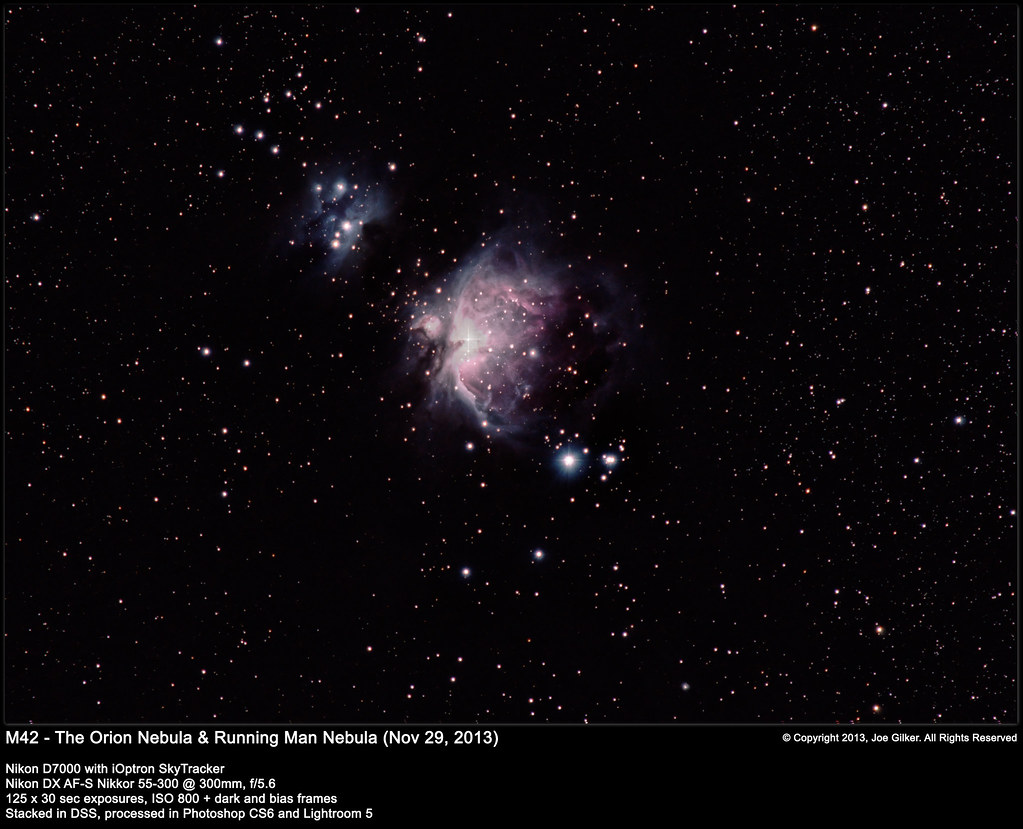

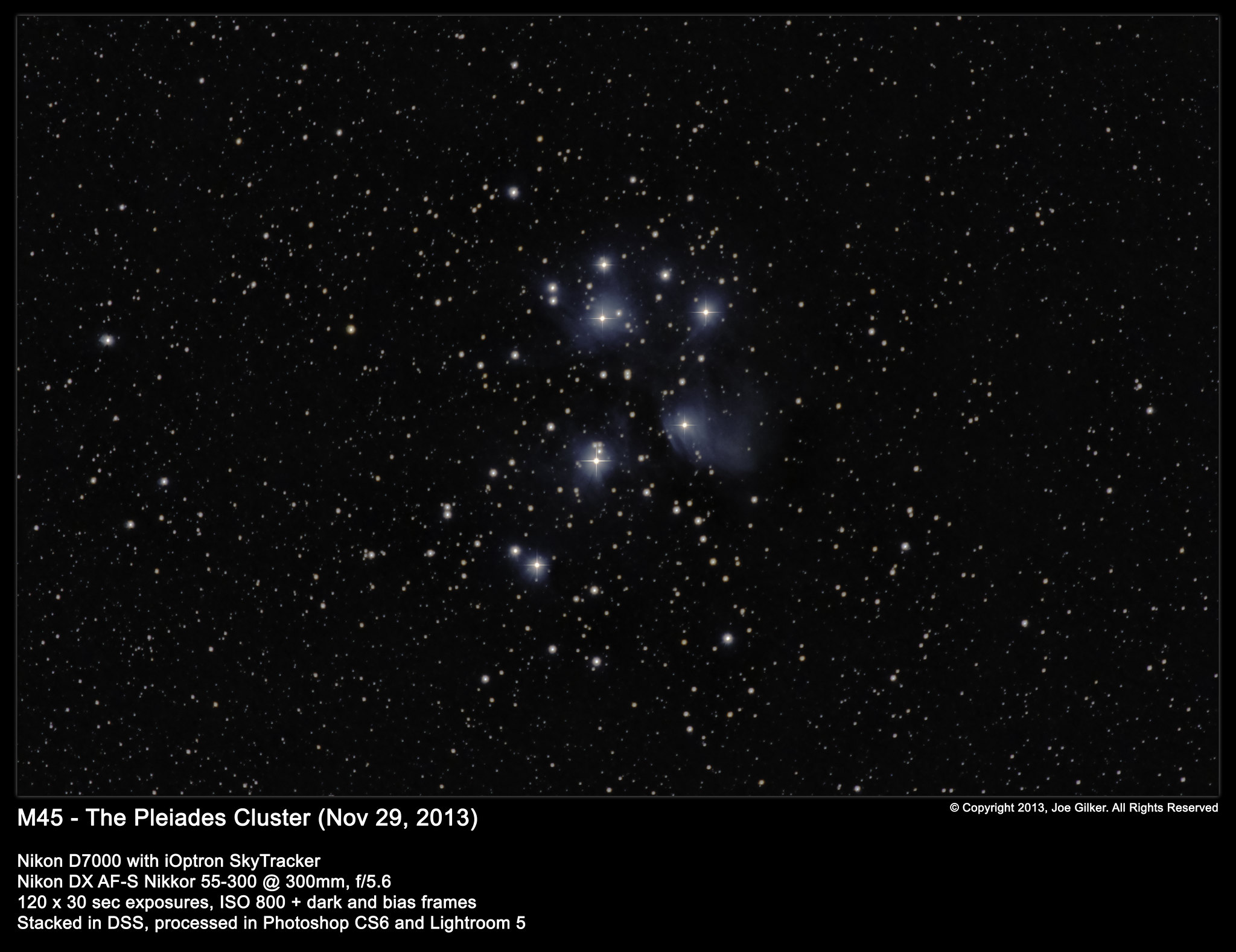

In the image below, you can see 4 images. The ones on the left are the starting point for editing. The voodoo here is taking that dull, dark image and bringing out the hidden pixels. Yes, all the data seen in the right hand images are in the images on the left. But the details are faint. The images on the right are the result of stretching colours, adjusting contrast, and adjusting colour balances. There are other tricks and tools, of course, but that’s the basic crux of it. No data is added or removed from the original dull image. It’s just a matter of brightening the details while darkening the background. The final results really do look like magic – black magic.

That’s the real reason I refer to it as the “dark arts”. Clear skies.